What is the LCA Tejas?

The LCA (Light Combat Aircraft) Tejas is a single-engine, 4.5 generation, all weather multi-role combat aircraft designed and developed by the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) and manufactured by the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) primarily for the Indian Air Force and the Indian Navy’s Aviation Arm. It is the smallest and lightest aircraft in its class of fighters. It uses the General Electric GE F404-IN20 engine, a variant of the GE F404 class of engines.

A history of the LCA Project:

The origins of the LCA Project lie in the 1980s. The Indian Air Force wanted to replace its aging MiG 21 fighters. After a submission of the Air Staff Requirements by the Air Force, the government allocated funds for the LCA program. Ambitious goals were set for indigenization of crucial components. This includes

the Fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system (electronic controls rather than manual controls),

the multi-mode pulse-doppler radar (a radar system that determines targets using pulse-timing techniques. In simple terms, it makes occasional scans rather than a continuous emission of radio wave frequencies), and

An afterburning turbofan engine.

These were to be indigenously designed and manufactured. Of these,

An indigenously developed FBW System was integrated on the Tejas. It was delayed, but successful.

The Pulse-doppler radar was replaced by an AESA (Active Electronically Scanned Array) Radar which is more resistant to electronic jamming. Currently, most Tejas aircraft are equipped with the Israeli Elta 2052 Radar as an interim solution.Future aircraft will be equipped with the indigenous UTTAM Radar, once it undergoes testing and integration. This is a partial success, but the ADA did not let delays in the Radar hinder the rest of the project.

The indigenous engine, known as the Kaveri, faced teething issues and massive delays and was eventually replaced by the GE F404 Engine.

Variants of the LCA:

As of today, there are 3 operational variants of the LCA.

The Tejas Mk1 is the first variant of the Tejas. It had 32 orders that have been delivered.

2. The Tejas Mk1A is the upgraded version of the Tejas Mk1. It is equipped with a jammer, radar warning receiver, and an externally mounted Electronic Countermeasure device. It also uses a larger share of indigenously manufactured components.

3. The Tejas Trainer, which is a two seater trainer variant.

There are 2 naval variants still under development, one combat and one trainer. The naval combat variant will have the ability to take-off from aircraft carriers and its prototype has already been tested on the INS Vikramaditya. This improves India’s long range power projection capabilities. Whether India should invest in aircraft carriers as opposed to submarines, is a different matter.

The Tejas Mk2 is a variant of the Tejas that is under development. It will have an increased size and payload capacity.

Issues faced with the LCA:

1: The Engine:

The first issue was the power plant of the fighter. Initially, the Kaveri Engine was to be used for the Tejas. However, it faced teething issues such as degraded performance at high altitudes, insufficient thrust, and excessive weight which would have reduced the Tejas’ Payload capacity. Engine development is a very complex endeavour. For example, the Chinese COMAC relies on western engines for its operations. Fortunately, the Aircraft Development team was willing to compromise. The Kaveri was replaced with the GE-F404 engines. As for the Engine development team, their efforts have not gone in vain. The Kaveri will be deployed on future unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). UAVs are much lighter and this makes the Kaveri more suitable for them.

2. Delays:

The development of the LCA has thrown up a lot of issues for its design and development team. The Indian Government had, in all its wisdom, set very ambitious targets for indigenization of the aircraft. This caused a lot of delays in the project and the deployment of the Tejas. The first flight was in 2001, and yet, it took another 15 years for the first planes to be inducted (2016). It was supposed to replace the MiG 21, MiG 29, and the Jaguar aircraft. However, until the development of the Tejas was complete, these aging aircraft would have to be kept operational. The MiG-21s are especially prone to crashing (India lost about half of its MiG 21 fleet to crashes, as well as a lot of experienced pilots). To this day, the Indian Air Force is forced to fly these three variants at exorbitant maintenance costs. However, the team learned its lessons through the development cycle. If domestic components weren’t good enough, they were replaced with foreign ones.

3. The radar:

The development of the Tejas took so long that Radar and radar-jamming technology had advanced dramatically. Pulse-Doppler Radars are susceptible to jamming while AESA Radars are relatively resistant. The DRDO developed the Uttam AESA Radar in 2012, and HAL decided to equip the Tejas Mk1A with the new radar. However, the radar is still under the testing phase and will take some time before it is operational. This prompted DRDO to deploy the Israeli Elta Radar until the Uttam is ready.

4. The Airframe:

The LCA Tejas is the smallest and lightest aircraft of its class. This can be a massive disadvantage when fielding the aircraft into combat. Multi-role combat aircraft can only be multi-role if the airframe can carry multiple weapons suites.

The beauty of modern military aviation lies in the fact that the role of an aircraft can be changed by simply swapping out its weapons suite.

Interceptors would require rapid shooting cannons which are more versatile in close combat situations.

Attack bombers would require guided missiles or unguided bombs to carry out bombing roles.

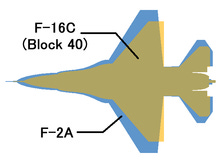

However, the small airframe limits the number of weapons that the Tejas can carry. It also reduces the number of electronic warfare systems that can be deployed on each aircraft. With advances in technology, electronic warfare capabilities are more and more important. Jamming and radar warning can give one side a significant advantage over its rivals. This means that a small airframe significantly restricts the flexibility of a platform and makes it more vulnerable to enemy aircraft. It is for this very reason that the Japanese Mitsubishi F-2, is about 25% larger than the F-16, the plane on which it is based.

5. Limited Payload:

The LCA Tejas has the smallest payload of all aircraft in its class. This also restricts the number of weapons it can carry in terms of weightage. Existing missile platforms that India uses for its Rafales and Su-30MKIs would also have to be modified to reduce their size and weightage. This would also reduce the range of these weapons which is detrimental, especially for beyond visual range (BVR) weapons.

6. A plane for a different era:

The development of the LCA has thrown up a lot of issues for its design and development team. The Indian Government had, in all its wisdom, set very ambitious targets for indigenization of the aircraft. This caused a lot of delays in the project and the deployment of the Tejas. The project was commissioned in 1983, when the transition to 4th generation aircraft had already started across the world. It took 18 years for the Tejas to take its first test flight (2001). By this time, the USA’s first fifth-generation aircraft, the F-117 Nighthawk, had already been deployed in combat over Serbia in 1999. It then took another 15 years for the first squadron to be completely operational (2006). It was supposed to replace the MiG-21, MiG-27, and Jaguar aircraft. However, until the development of the Tejas was complete, these aging aircraft would have to be kept operational. The MiG-21s are especially prone to crashing (India lost about half of its MiG-21 fleet to crashes, as well as a lot of experienced pilots). To this day, the Indian Air Force is forced to fly these variants at exorbitant maintenance costs.

Even the upgraded Mk1A is a fourth-generation aircraft at the end of the day. Meanwhile, the USA has started retiring the F-117 from combat roles. Had the Tejas been deployed earlier, it might have been easier to identify issues with the jet and correct them. This would have led to a faster development cycle and allowed scientists to build upon the expertise gained from the LCA Project.

However, the team learned its lessons through the development cycle. If domestic components weren’t good enough, they were replaced with foreign ones.

Strength in Numbers:

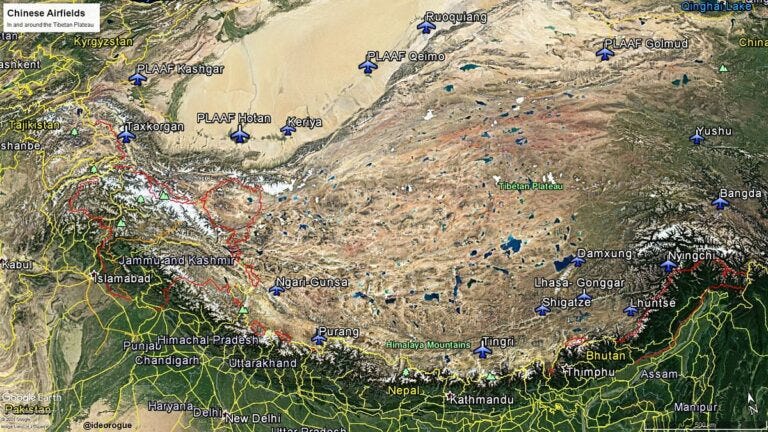

These limitations mentioned above might paint a gloomy picture, but that is not necessarily the case. The Indian Air Force is the main user of the LCA Tejas. Its main usage would be in air-to-air combat along the India-Pakistan and India-Tibet borders. In case of a war, the primary goal for the Indian Air Force is to achieve air superiority over Indian and Pakistani skies. The Tejas, in tandem with the Sukhoi 30MKIs, Rafales, and an increasing number of drones, will be crucial. In the event of a war with China, the LCA could only realistically be used to keep the skies of Tibet contested, since the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) has a much larger number of aircraft. Here, the Tejas is limited by its range and payload.

Here it needs to match Pakistani JF-17s and Chinese J-10s in terms of capability. Given that the two aircraft are more capable designs based on firepower per plane and range, the IAF would have to field a larger number of the LCAs to match them. Fortunately, in this scenario, geography is a massive disadvantage for the Chinese. The performance of J-10s reduces a lot when deployed from bases in the high altitudes of the Tibetan plateau. The air is less dense and hence, more fuel is needed for the plane to take off, reducing its effective range. Indian bases are mostly located in the North Indian plains with the exception of Ladakh and Himachal, which are still far lower than the Chinese bases in Tibet.

Given the restrictions that the Tejas faces, as outlined above, it is evident that the Tejas isn’t the best fighter aircraft of its class. However, the calculus of defence indigenisation is the acceptance of an inferior product. In return, the organization working on it will continue to improve the quality of the product over a long time frame.

There are some solutions to mitigate the issues that the Tejas faces. The IAF will have to field a larger number of the Tejas in combat. Especially in aerial dogfights, which is what the LCA is most likely to be used in, the amount of firepower brought to the battlefield is crucial. This means India would have to produce at least 500 of the Tejas Mk1A and Mk2 in the next 10 years, in order to

Replace its aging MiG 21s, Jaguars, and MiG 29s, and Mirage 2000s

Compensate for the reduced payload capacity of each of these planes

The DRDO should work towards new versions of the Astra and the BrahMos Missiles, that would enhance the combat prowess of the Tejas.

The Future of The LCA Tejas:

HAL and DRDO have plans to develop the Tejas Mark 2, one variant for the Air Force and another for the Navy. For the Mk1A, The Indian Government also plans to outsource more of the component manufacturing to private sector companies to reduce cost and provide room for greater innovation. This narrows the focus for the DRDO down to R&D, and for HAL to assemble the aircraft components together. A total of 220 planes have been ordered between the Mk1, Mk1A, and the trainer variant. These are split in 3 orders. There are also plans to order some 210 Units of the Mk2 once it is operational by 2028.

Possible Foreign Orders:

The LCA Tejas has been sent to a few international air shows, like Dubai 2023, and Singapore 2022. Apparently, Malaysia had shortlisted the Tejas for an order of up to 18 aircraft but was cancelled. Argentina, Botswana, Nigeria, Philippines, and Egypt have also reportedly shown interest in the Tejas. HAL is said to have offered a sweet deal to Egypt involving technology transfer and indigenous manufacturing in Egypt if the order is big enough. Philippines is a promising candidate as it has already purchased India’s BrahMos Missile. Another potential candidate here could be Armenia. India and Armenia have enjoyed growing military ties as outlined before. With Azerbaijan purchasing the JF-17, it makes sense now more than ever for India to sell the Tejas to Armenia. If India can get a stronger weapons suite going for the Tejas, or improve its dogfighting capabilities, Armenia’s Air Force could be equipped with a good number of the Tejas aircraft, which would be a major win for India.

Conclusion:

The LCA Tejas is a promising project, albeit one with a long, challenging, and tumultuous journey, marked with several lessons and setbacks. However, it has also contributed a great deal to IndianAerospace capabilities. It might not be the best of its class, but it is good enough. If deployed with the correct tactics, it could easily go toe-to-toe with its primary adversaries. It will be interesting to see if Tejas is a repeat of the HAL Marut. It looks like lessons have been learned this time, as the DRDO and the ADA seem to be more willing to compromise if the indigenization doesn’t seem immediately possible. The aircraft has been designed and developed. It is up to the Defence Ministry to place orders and push the aircraft towards greater maturity. Hopefully, this time around, the Indian Government doesn’t kill future programs which could utilize expertise, know-how, and know-why gained from the Tejas. The DRDO does have a few projects, including the Fifth Generation AMCA and the TED-BF. The LCA will be invaluable in shapingIndia’s future aerial combat capabilities.